Yakama Nation Tells DOE to Clean Up Nuclear Waste

YAKAMA NATION, Washington State, U.S., Apr 14 (IPS) - The Department of Energy (DOE), politicians and CEOs were discussing how to warn generations 125,000 years in the future about the radioactive waste at Hanford Nuclear Reservation, considered the most polluted site in the U.S., when Native American anti-nuclear activist Russell Jim interrupted their musings: "We'll tell them."

He tells IPS "they looked around and saw me. I said, ‘We've been here since the beginning of time, so we will be here then.' That was when they knew they'd have a fight on their hands."3

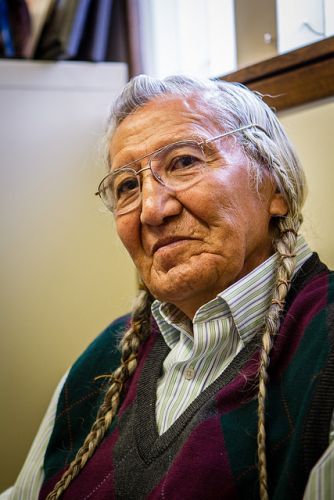

With his long braids, the 78-year-old director of the Environmental Restoration & Waste Management Programme (ERWM) for the Yakama tribes cuts a striking figure, sitting calmly in his office located on the arid lands of his sovereign nation.

The Yakama Reservation in southeast Washington has 1.2 million acres with 10,000 federally recognised tribal members and an estimated 12,000 feral horses roaming the desert steppe. Down from the 12 million acres ceded by force to the U.S. government in 1855, it is just 20 miles west from the Hanford nuclear site.

Though the nuclear arms race ended in 1989, radioactive waste is the legacy of the various sites of the former Manhattan Project spread across the U.S.

While the Yakama have successfully protected their sacred fishing grounds from becoming a repository for nuclear waste from other project sites by invoking the treaty of 1855 which promises access to their "usual and accustomed places," Hanford is far from clean, though the DOE promised to restore the land.

"The DOE is trying to reclassify the waste as ‘low activity.' They are trying to leave it here and bury it in shallow pits. Scientists are saying that it needs to be buried deep under the ground," Jim explains.

Tom Carpenter of Hanford Challenge watchdog group tells IPS "it is a battle for Washington State and the tribes to get the feds to keep their promise to remove the waste. There are 42 miles of trenches that are 15 feet wide and 20 feet deep full of boxes, crates and vials of waste in unlined trenches."

There are a further 177 underground tanks of radioactive waste and six are leaking. Waste is supposed to be moved within 24 hours from leak detection or whenever is "practicable" but the contractors say there is not enough space.

Three whistleblowers working on the cleanup raised concerns and were fired. Closely followed by a local news station, it is an issue that is largely neglected by mainstream media and the Yakama's fight seems all but ignored.

"We used to have a media person on staff but the DOE says there is no need as ‘everything is going fine," says Russell Jim. His department lost 80 percent of its funding in 2012 after cutbacks. His tribe doesn't fund ERWM, the DOE does. "The DOE crapped it up, so they should pay for it."

Russell Jim, Yakama Elder and Director of Environmental Restoration & Waste Management Program (ERWM) for the Yakama Nation. Credit: Jason E. Kaplan/IPS

Russell Jim, Yakama Elder and Director of Environmental Restoration & Waste Management Program (ERWM) for the Yakama Nation. Credit: Jason E. Kaplan/IPS

But everything is not fine. With radioactive groundwater plumes making their way toward the river, the Yakama and watchdog groups says it is an emergency. Some plumes are just 400 yards from the river where the tribe accesses Hanford Reach monument, according to treaty rights.

Hanford Reach nature reserve, a buffer zone for the site, is the Columbia's largest spawning grounds for wild fall Chinook salmon

Washington State reports highly toxic radioactive contamination from uranium, strontium 90 and chromium in the ground water has already entered the Columbia River.

"There are about 150 groundwater ‘upwellings' in the gravel of the Columbia River coming from Hanford that young salmon swim around," explains Russell Jim.

"Helen Caldecott told us in 1997 that if we eat fish from the Columbia, we'll die," he adds.

Callie Ridolfi, environmental consultant to the Yakama, tells IPS their diet of 150 to 519 grammes of fish a day, nearly double regional tribal averages and far greater than the mainstream population, puts them at greater risk, with as much as a one in 50 chance of getting cancer from eating resident fish.

Migratory fish like salmon that live in the ocean most of their lives are less affected, unlike resident fish.

According to a 2002 EPA study on fish contaminants, resident sturgeon and white fish from Hanford Reach had some of the highest levels of PCBs.

Last year, Washington and Oregon states released an advisory for the 150-mile heavily dammed stretch of the Columbia from Bonneville to McNary Dam to limit eating resident fish to once a week due to PCB toxins.

Fisheries manager at Mike Matylewich at Columbia River Inter Tribal Fish Commission (CRITFC), says, "Lubricants containing PCBs were used for years, particularly in transformers, at hydroelectric dams because of the ability to withstand high temperatures.

"The ability to withstand high temperatures contributes to their persistence in the environment as a legacy contaminant," he tells IPS.

While the advisory does not include the Hanford Reach, the longest undammed stretch of the Columbia, Russell Jim doubts it's safe.

"The DOE tells congress the river corridor is clean. It's not clean but they are afraid of damages being filed against them." A cancer survivor, Jim's tribe received no compensation for damages from radioactive releases from 1944 to 1971 into the Columbia as high as 6,300,000 curies of Neptunium-239.

Steven G. Gilbert, a toxicologist with Phyisicnas for Social Responsbility, tells IPS there is a lack transparency and data on the Hanford cleanup. "It is a huge problem," he says, adding that contaminated groundwater at Hanford still interacts with the Columbia River, based on water levels.

Though eight of the nine nuclear reactors next to the river were decommissioned, the 1,175-megawatt Energy Northwest Energy power plant is still functioning

"Many people don't know there is a live nuclear reactor on the Columbia. It's the same style as Fukushima," Gilbert explains.

In the middle of the fight are the tribes, which are sovereign nations. Russell Jim says they are often erroneously described as "stakeholders" when they are separate governments.

"We were the only tribe to take on the nuclear issue and testify at the 1980 Senate subcommittee. In 1982 we immediately filed for affected tribe status. The Umatilla and the Nez Perce tribes later joined."

Yucca Mountain was earmarked by congress as a nuclear storage repository for Hanford and other sites' waste but the plan was struck down by the president. Southern Paiute and Western Shoshone in the region filed for affected status.

The Waste Isolation Pilot Plant (WIPP) in New Mexico was slated to take waste from Hanford but after a fire in February, the site is taking no more waste. The Bulletin of Atomic Scientists has expressed concern about the lack of storage options.

The U.S. has the largest stockpile of spent nuclear fuel globally - five times that of Russia.

"The best material to store waste in is granite and the northeast U.S. has a lot of granite. An ideal site was just 30 miles from the capital, but that is out," says Russell Jim with a wry smile, considering its proximity to the White House.

He does not plan to give up. "We are the only people here who can't pick up and move on."

© Inter Press Service (2014) — All Rights ReservedOriginal source: Inter Press Service

Global Issues

Global Issues