New Plan Would Aggravate the Troubles of Chile’s Beleaguered Pensioners

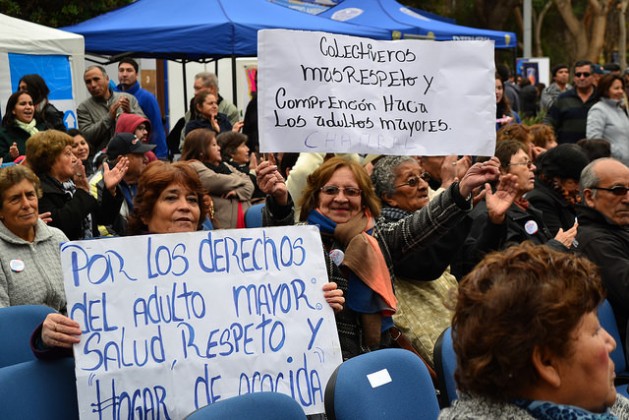

SANTIAGO, Jul 24 (IPS) - The already precarious situation of pensioners in Chile will get even worse if a controversial initiative is approved. Under the new plan, the elderly would mortgage their homes to increase their meagre pensions, most of which come from prívate pension funds, and which average 230 dollars a month.

"This plan is a ruse, a dirty trick," Nuvia Zambrano, a pensioner, told IPS. "If we can hardly survive on our pensions, how could we afford the mortgage payments? Our homes would be left to the banks," said the former high school biology teacher who retired 10 years ago.

The reverse mortgage plan, presented by opposition legislators and backed by governing coalition lawmakers, would create a contract between the homeowner and a government institution. Based on the value of the property, and the calculation of the owner's life expectancy, the period for payment and monthly payments until the end of their life would be set.

The pensioners would continue to live in their homes until they died. After that, their heirs could buy back the property for the amount already paid or hand it over to finish paying off the mortgage.

But experts say the new plan would create "a new psychological burden for older adults," who already live their last years in debt and with pensions that in many cases do not cover the cost of living.

Chile's pension system, based on mandatory individual retirement accounts, was introduced in 1981 by the military dictatorship of General Augusto Pinochet (1973-1990).

Under the system, workers deposit at least 10 percent of their wages into personal accounts managed by private pension funds (AFPs).

The capital is then invested in shares in large companies and banks in Chile or abroad, which generate returns.

According to the Fundación Sol, a labour think tank, the pension funds have earned more than 5.8 bilion dollars so far, from the lucrative business of mandatory individual accounts.3

Meanwhile, nine out of 10 pensioners in Chile receive less than 230 dollars a month, equivalent to 66 percent of the monthly mínimum wage of 373 dollars, according to the respected think tank.

Prior to the pension reform, Chile had a public pay-as-you-go system.

"Back then they said the new system was wonderful," Marianela Zambrano, Nuvia's sister, told IPS. "I was just coming back from exile in Denmark and didn't have much idea of how it worked.

"Now I know it's the theft of a century, a disgusting theft, an injustice," she said angrily.

The 62-year-old English teacher who worked for over 30 years receives a pension today of just 334 dollars a month. Her rent payment alone eats up 186 dollars.

"Our pensions don't cover the cost of living; they might as well just give us poison instead, because you die of hunger anyway," she said, bitterly.

Today, only a handful of countries have pension systems similar to Chile's: Dominican Republic, Israel, Nigeria, Maldives, Malawi, Kosovo and Australia – although Australia ensures a basic pension of 1,000 dollars a month for many of the country's older adults.

Among Chile's neighbours, Argentina switched back from a mixed system to a traditional pay-as-you-go scheme, in 2008.

Uruguay, meanwhile, has a mixed system consisting of a public pay-as-you-go regime combined with individual accounts. It was modified in 2005 though a labour reform, which increased wages and gave trade unions a stronger role.

In Chile, on the other hand, the system put in place by the dictatorship in 1981 has been operating for 35 years and the democratic governments that have ruled the country since 1990 have shown no intention of modifying it.

The centre-left governments, including the current administration headed by socialist President Michelle Bachelet, and the administration of her right-wing predecessor Sebastián Piñera (2010-2014), only introduced measures to ensure pensions for those excluded by the AFPs.

"This system has been tremendously successful with regard to one objective: financing the economy, injecting fresh capital to capitalise companies or economic groups," Fundación Sol economist Gonzalo Durán told IPS.

In this South American country of 17.5 million people, women retire at the age of 60 and men at 65. But in practice, both men and women tend to work until at least the age of 70.

The prívate pension funds determine life expectancy, which varies depending on gender and other factors, using actuarial life tables.

Life expectancy in Chile stands at 83 years for women and 76 for men, according to the World Health Organisation (WHO).

But according to the AFPs, Chilean women have a life expectancy of 89 and men, 85.

Each pensioner's projected lifespan, and the resulting number of monthly payments, are calculated according to the life table. Their heirs can later inherit a monthly pension, which the AFP determines based on what is left of the pensioner's lifelong savings. That depends on factors such as the educational level of the sons and daughters.

According to the Superintendencia de Pensiones, the government agency that oversees the pension funds, in December 2014 nearly seven of every 10 Chileans between the ages of 55 and 60 had roughly 31,000 dollars in their individual accounts – an amount that does not ensure a pension of over 155 dollars a month.

"The pension system plays a major role in the concentration of income and the problem of inequality, which we have to hold a debate about," said Durán.

He added that the system is a key component of Chile's neoliberal model.

Durán said the private pension fund system is not meeting the goal of providing social security in Chile, where the estimated cost of a family's basic needs is 264 dollars a month, and medications can cost three times what they cost in Argentina or Peru.

As a result, older adults are impoverished and have no choice but to continue working after retirement to compensate for their small pensions. They are also in debt.

The most important reform of Chile's pension system was carried out in 2008, during President Bachelet's first term (2006-2010). It benefited the poorest 60 percent of the elderly. Her administration introduced a 133-dollar a month public pension for people who never paid into a retirement scheme, such as street vendors, the self-employed, homemakers or small farmers. In addition, the lowest pensions were topped up.

This scenario "is suspicious," said Durán, because while pensions are low, "the system brings big benefits to prívate companies" – unlike a pay-as-you-go scheme.

"There is a legitimate suspicion that they don't want to change the system in order not to deprive the companies of the profits they are earning. If that turns out to be true, it's very serious," he said.

For now the government says it will not back the controversial bill. But the lawmakers who are behind it say they will continue to push for it to be passed. And it has support on both sides of the political spectrum.

Edited by Estrella Gutiérrez/Translated by Stephanie Wildes

© Inter Press Service (2015) — All Rights ReservedOriginal source: Inter Press Service

Global Issues

Global Issues