A Primer on Neoliberalism

Author and Page information

- This page: https://www.globalissues.org/article/39/a-primer-on-neoliberalism.

- To print all information (e.g. expanded side notes, shows alternative links), use the print version:

Neoliberalism is promoted as the mechanism for global trade and investment supposedly for all nations to prosper and develop fairly and equitably. Margaret Thatcher’s TINA acronym suggested that There Is No Alternative to this. But what is neoliberalism, anyway?

This section attempts to provide an overview. First, a distinction is made between political and economic liberalism. Then, neoliberalism as an ideology for how to best structure economies is explained. Lastly, for important context, there is a quick historical overview as to how this ideology developed.

On this page:

Political versus Economic Liberalism

There is an important difference between liberal politics and liberal economics. But this distinction is usually not articulated in the mainstream.

As summarized here by Elizabeth Martinez and Arnoldo Garcia:

Liberalismcan refer to political, economic, or even religious ideas. In the U.S. political liberalism has been a strategy to prevent social conflict. It is presented to poor and working people as progressive compared to conservative or Right wing. Economic liberalism is different. Conservative politicians who say they hateliberals— meaning the political type — have no real problem with economic liberalism, including neoliberalism.

Neo-Liberalism?, National Network for Immigrant and Refugee Rights, January 1, 1997 (posted at CorpWatch.org)

The web site, Political Compass, also highlights these differences very well.

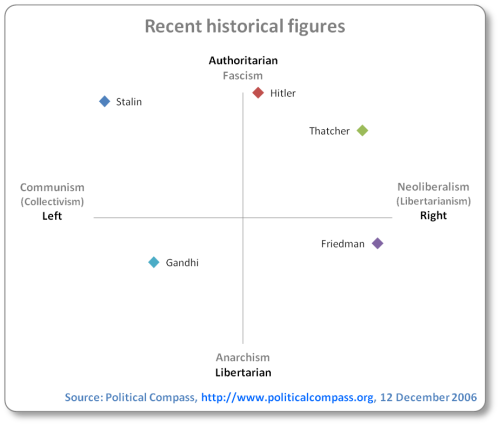

They show Left and Right as an economic scale, with Authoritarian and Libertarian making up the political scale, crossing the economic scale resulting in quadrants:

In addition, they note that, despite popular perceptions, the opposite of fascism is not communism but anarchism (ie liberal socialism), and that the opposite of communism (i.e. an entirely state-planned economy) is neo-liberalism (i.e. extreme deregulated economy).

This is made clear by another chart they have:

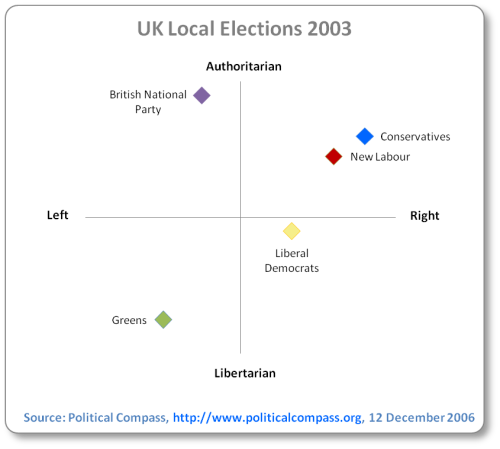

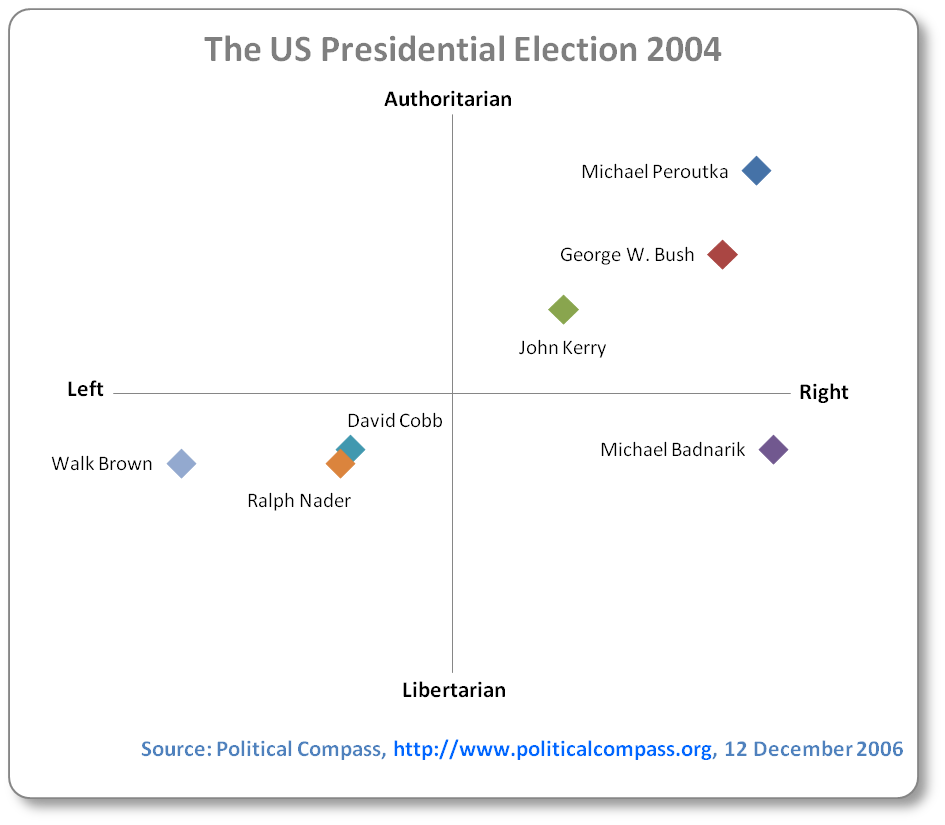

A few other charts of theirs are of interest:

1) The positions of some well-known political figures in the world

(In the above, it is interesting to note how most of the world’s influential leaders, from the wealthiest and most poweful countries all fall into the area of authoritarian-right.)

2) A look at English political parties and how they fair (even the left

ones.)

3) It is also interesting to see how the three main British political parties have changed over time, as Political Compass shows:

4) The last US elections (2004) show the political spectrum between John Kerry and George W. Bush was note that wide:

They also make a distinction about neo-conservatives and neoliberals:

U.S. neo-conservatives, with their commitment to high military spending and the global assertion of national values, tend to be more authoritarian than hard right. By contrast, neo-liberals, opposed to such moral leadership and, more especially, the ensuing demands on the tax payer, belong to a further right but less authoritarian region. Paradoxically, the "free market", in neo-con parlance, also allows for the large-scale subsidy of the military-industrial complex, a considerable degree of corporate welfare, and protectionism when deemed in the national interest. These are viewed by neo-libs as impediments to the unfettered market forces that they champion.

What the above highlights then, is that in some countries, discourse on these topics may appear to fit into left-right balance, but when looked at a more global scale, the range of discourse may be narrow. Economic issues such as globalization, especially as it affects third world countries as well as those in the first world, require a broader range of discussion.

Neoliberalism is...

Neoliberalism, in theory, is essentially about making trade between nations easier. It is about freer movement of goods, resources and enterprises in a bid to always find cheaper resources, to maximize profits and efficiency.

To help accomplish this, neoliberalism requires the removal of various controls deemed as barriers to free trade, such as:

- Tariffs

- Regulations

- Certain standards, laws, legislation and regulatory measures

- Restrictions on capital flows and investment

The goal is to be able to to allow the free market to naturally balance itself via the pressures of market demands; a key to successful market-based economies.

As summarized from What is Neo-Liberalism

? A brief definition for activists by Elizabeth Martinez and Arnoldo Garcia from Corporate Watch, the main points of neoliberalism includes:

- The rule of the market — freedom for capital, goods and services, where the market is self-regulating allowing the

trickle down

notion of wealth distribution. It also includes the deunionizing of labor forces and removals of any impediments to capital mobility, such as regulations. The freedom is from the state, or government. - Reducing public expenditure for social services, such as health and education, by the government

- Deregulation, to allow market forces to act as a self-regulating mechanism

- Privatization of public enterprise (things from water to even the internet)

- Changing perceptions of public and community good to individualism and individual responsibility.

Overlapping the above is also what Richard Robbins, in his book, Global Problems and the Culture of Capitalism (Allyn and Bacon, 1999), summarizes (p.100) about some of the guiding principles behind this ideology of neoliberalism:

- Sustained economic growth is the way to human progress

- Free markets without government

interference

would be the most efficient and socially optimal allocation of resources - Economic globalization would be beneficial to everyone

- Privatization removes inefficiencies of public sector

- Governments should mainly function to provide the infrastructure to advance the rule of law with respect to property rights and contracts.

At the international level then we see that this additionally translates to:

- Freedom of trade in goods and services

- Freer circulation of capital

- Freer ability to invest

The underlying assumption then is that the free markets are a good thing. They may well be, but unfortunately, reality seems different from theory. For many economists who believe in it strongly the ideology almost takes on the form of a theology. However, less discussed is the the issue of power and how that can seriously affect, influence and manipulate trade for certain interests. One would then need to ask if free trade is really possible.

From a power perspective, free

trade in reality is seen by many around the world as a continuation of those old policies of plunder, whether it is intended to be or not. However, we do not usually hear such discussions in the mainstream media, even though thousands have protested around the world for decades.

Today then, neoliberal policies are seeing positives and negatives. Under free enterprise, there have been many innovative products. Growth and development for some have been immense. Unfortunately, for most people in the world there has been an increase in poverty and the innovation and growth has not been designed to meet immediate needs for many of the world’s people. Global inequalities on various indicators are sharp. For example,

- Some 3 billion people — or half of humanity — live on under 2 dollars a day

- 86 percent of the world’s resources are consumed by the world’s wealthiest 20 percent

- (See this site’s page on poverty facts for many more examples.)

Joseph Stiglitz, former World Bank Chief Economist (1997 to 2000), Nobel Laureate in Economics and now strong opponent of the ideology pushed by the IMF and of the current forms of globalization, notes that economic globalization in its current form risks exacerbating poverty and increasing violence if not checked, because it is impossible to separate economic issues from social and political issues.

And as J.W. Smith has argued:

One cannot separate economics, political science, and history. Politics is the control of the economy. History, when accurately and fully recorded, is that story. In most textbooks and classrooms, not only are these three fields of study separated, but they are further compartmentalized into separate subfields, obscuring the close interconnections between them.

Issues such as the criticisms of free

trade, of protests around the world, and many others angles are discussed on this section’s subsequent pages.

The history of neoliberalism and how it has come about is worth looking at first, however, to get some crucial context, and to understand why so many people around the world criticize it.

Brief overview of Neoliberalism’s History: How did it develop?

Free Markets Were Not Natural. They Were Enforced

The modern system of free trade, free enterprise and market-based economies, actually emerged around 200 years ago, as one of the main engines of development for the Industrial Revolution.

In 1776, British economist Adam Smith published his book, The Wealth of Nations. Adam Smith, who some regard as the father of modern free market capitalism and this very influential book, suggested that for maximum efficiency, all forms of government interventions in economic issues should be removed and that there should be no restrictions or tariffs on manufacturing and commerce within a nation for it to develop.

For this to work, social traditions had to be transformed. Free markets were not inevitable, naturally occurring processes. They had to be forced upon people. John Gray, professor of European thought at the London School of Economics, a prominent conservative political thinker and an influence on Margaret Thatcher and the New Right in Britain in the 1980s, notes:

Mid-nineteenth century England was the subject of a far-reaching experiment in social engineering. Its objective was to free economic life from social and political control and it did so by constructing a new institution, the free market, and by breaking up the more socially rooted markets that had existed in England for centuries. The free market created a new type of economy in which prices of all goods, including labour, changed without regard to their effects on society. In the past economic life had been constrained by the need to maintain social cohesion. It was conducted in social markets — markets that were embedded in society and subject to many kinds of regulation and restraint. The goal of the experiment that was attempted in mid-Victorian England was to demolish these social markets, and replace them by deregulated markets that operated independently of social needs. The rupture in England’s economic life produced by the creation of the free market has been called the Great Transformation.

A detailed insight into this process of transformation is revealed by Michael Perelman, Professor of Economics at California State University. In his book The Invention of Capitalism (Duke University Press, 2000), he details how peasants did not willingly abandon their self-sufficient lifestyle to go work in factories.

- Instead they had to be forced with the active support of thinkers and economists of the time, including the famous originators of classical political economy, such as Adam Smith, David Ricardo, James Steuart and others.

- Contradicting themselves, as if it were, they argued for government policies that deprived the peasants their way of life of self-provision, to coerce them into waged labor.

- Separating the rural peasantry from their land was successful because of

ideological vigor

from people like Adam Smith, and because of arevision of history

that created an impression of a humanitarian heritage of political economy; an inevitability to be celebrated. - This revision, he also noted has evidently

succeeded mightily.

Rooted in Mercantilism

Adam Smith’s work did, however, expose the previous fraud that was the mercantilist system, which enriched the imperial powers at the expense of others. This mercantilism had its roots in the Middle and Dark Ages of Europe, many hundreds of years earlier and also parallels various methods used by empires throughout history (including today) to control their peripheries and appropriate wealth accordingly. Furthermore, as J.W. Smith argues, even though it is claimed to be Adam Smith free trade, neoliberalism was and is mercantilism dressed up with more friendly rhetoric, while the reality remains the same as the mercantilist processes over the last several hundred years:

The powerful throughout the past centuries not only claimed an excessive share of the wealth of nature which was properly shared by all within the community, through the unequal trades of mercantilism they claimed an excessive share of the wealth on the periphery of their trading empires. Adam Smith describes mercantilism for us:

[Mercantilism’s] ultimate object… is always the same, to enrich the country [city or state] by an advantageous balance of trade. It discourages the exportation of the materials of manufacture [tools and raw material], and the instruments of trade, in order to give our own workmen an advantage, and to enable them to undersell those of other nations [cities] in all foreign markets: and by restraining, in this manner, the exportation of a few commodities of no great price, it proposes to occasion a much greater and more valuable exportation of others. It encourages the importation of the materials of manufacture, in order that our own people may be enabled to work them up more cheaply, and thereby prevent a greater and more valuable importation of the manufactured commodities.

William Appleman Williams describes mercantilism at its zenith:

The world was defined as known and finite, a principle agreed upon by science and theology. Hence the chief way for a nation to promote or achieve its own wealth and happiness was to take them away from some other country.When the injustice of mercantilism was understood, it became too embarrassing and was replaced by the supposedly just Adam Smith free trade. But free trade as practiced by Adam Smith neo-mercantilists was far from fair trade. Adam Smith unequal free trade is little more than a philosophy for the continued subtle monopolization of the wealth-producing-process, largely through continued privatization of the commons of both an internal economy and the economies of weak nations on the periphery of trading empires. So long as weak nations could be forced to accept the unequal trades of Adam Smith free trade, they would be handing their wealth to the imperial-centers-of-capital of their own free will. In short, Adam Smith free trade, as established by neo-mercantilists, was only mercantilism hiding under the cover of free trade.

Colonialism and Imperialism Needed To Succeed

Free trade formed the basis of free enterprise for capitalists and up until the Great Depression of the 1930s was the primary economic theory followed in the United States and Britain. But from a global perspective, this free trade was accompanied by geopolitics making it look more like mercantilism. For both these nations (as well as others) to succeeded and remain competitive in the international arena, they had a strong foundation of imperialism, colonialism and subjugation of others in order to have access to the resources required to produce such vast wealth. As J.W. Smith notes above, this was hardly the free trade that Adam Smith suggested and it seemed like a continuation of mercantilist policies.

However, even during its prevalent times before the Second World War, neoliberalism had already started to show signs of increasing disparities between rich and poor.

Because of the Great Depression in the 1930s, an economist, John Maynard Keynes, suggested that regulation and government intervention was actually needed in order to provide more equity in development. This led to the Keynesian

model of development and after World War II formed the foundation for the rebuilding of the U.S-European-centered international economic system. The Marshall Plan for Europe helped reconstruct it and the European nations saw the benefits of social provisions such as health, education and so on, as did the U.S. under President Roosevelt’s New Deal.

In fact, the Bretton Woods Institutions (the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and World Bank) were actually designed with Keynesian policies in mind; to help provide international regulation and control of capital. As Susan George notes, when these institutions were created at Bretton Woods in 1944, their mandate was to help prevent future conflicts by lending for reconstruction and development and by smoothing out temporary balance of payments problems. They had no control over individual government’s economic decisions nor did their mandate include a license to intervene in national policy.

This is very different from what they are doing today.

In 1945 or 1950, if you had seriously proposed any of the ideas and policies in today’s standard neo-liberal toolkit, you would have been laughed off the stage at or sent off to the insane asylum. At least in the Western countries, at that time, everyone was a Keynesian, a social democrat or a social-Christian democrat or some shade of Marxist. The idea that the market should be allowed to make major social and political decisions; the idea that the State should voluntarily reduce its role in the economy, or that corporations should be given total freedom, that trade unions should be curbed and citizens given much less rather than more social protection — such ideas were utterly foreign to the spirit of the time. Even if someone actually agreed with these ideas, he or she would have hesitated to take such a position in public and would have had a hard time finding an audience.

However, as elites and corporations saw their profits diminish with this equalizing effect, economic liberalism was revived, hence the term neoliberalism

. Except, that this new form was not just limited to national boundaries, but instead was to apply to international economics as well. Starting from the University of Chicago with the philosopher-economist Friedrich von Hayek and his students such as Milton Friedman, the ideology of neoliberalism was pushed very thoroughly around the world.

Even before this though, there were indications that the world economic order was headed this way: the majority of wars throughout history have had economics, trade and resources at their core. The want for access to cheap resources to continue creating vast wealth and power allowed the imperial empires to justify military action, imperialism and colonialism in the name of national interests

, national security

, humanitarian

intervention and so on. In fact, as J.W. Smith notes:

The wealth of the ancient city-states of Venice and Genoa was based on their powerful navies, and treaties with other great powers to control trade. This evolved into nations designing their trade policies to intercept the wealth of others (mercantilism). Occasionally one powerful country would overwhelm another through interception of its wealth though a trade war, covert war, or hot war; but the weaker, less developed countries usually lose in these exchanges. It is the military power of the more developed countries that permits them to dictate the terms of trade and maintain unequal relationships.

As European and American economies grew, they needed to continue expansion to maintain the high standards of living that some elites were attaining in those days. This required holding on to, and expanding colonial territories in order to gain further access to the raw materials and resources, as well exploiting cheap labor. Those who resisted were often met with brutal repression or military interventions. This is not a controversial perception. Even U.S. President Woodrow Wilson recognized this in the early part of the 20th century:

Since trade ignores national boundaries and the manufacturer insists on having the world as a market, the flag of his nation must follow him, and the doors of the nations which are closed against him must be battered down. Concessions obtained by financiers must be safeguarded by ministers of state, even if the sovereignty of unwilling nations be outraged in the process. Colonies must be obtained or planted, in order that no useful corner of the world may be overlooked or left unused.

Richard Robbins, Professor of Anthropology and author of Global Problems and the Culture of Capitalism is also worth quoting at length:

The Great Global Depression of 1873 that lasted essentially until 1895 was the first great manifestation of the capitalist business crisis. The depression was not the first economic crisis [as there had been many for thousands of years] but the financial collapse of 1873 revealed the degree of global economic integration, and how economic events in one part of the globe could reverberate in others.…

The Depression of 1873 revealed another big problem with capitalist expansion and perpetual growth: it can continue only as long as there is a ready supply of raw materials and an increasing demand for goods, along with ways to invest profits and capital. Given this situation, if you were an American or European investor in 1873, where would you look for economic expansion?

The obvious answer was to expand European and American power overseas, particularly into areas that remained relatively untouched by capitalist expansion — Africa, Asia, and the Pacific. Colonialism had become, in fact, a recognized solution to the need to expand markets, increase opportunities for investors, and ensure the supply of raw material. Cecil Rhodes, one of the great figures of England’s colonization of Africa, recognized the importance of overseas expansion for maintaining peace at home. In 1895 Rhodes said:

I was in the East End of London yesterday and attended a meeting of the unemployed. I listened to the wild speeches, which were just a cry for

bread,bread,and on my way home I pondered over the scene and I became more than ever convinced of the importance of imperialism.… My cherished idea is a solution for the social problem, i.e., in order to save the 40,000,000 inhabitants of the United Kingdom from a bloody civil war, we colonial statesmen must acquire new lands for settling the surplus population, to provide new markets for the goods produced in the factories and mines. The Empire, as I have always said, is a bread and butter question. If you want to avoid civil war, you must become imperialist.As a result of this cry for imperialist expansion, people all over the world were converted into producers of export crops as millions of subsistence farmers were forced to become wage laborers producing for the market and required to purchase from European and American merchants and industrialists, rather than supply for themselves, their basic needs.

World War I was, in effect, a resource war as Imperial centers battled over themselves for control of the rest of the world. World War II was another such battle, perhaps the ultimate one. However, the former imperial nations realized that to fight like this is not the way, and became more cooperative instead.

Unfortunately, that cooperation was not for all the world’s interests primarily, but their own. The Soviet attempt of an independent path to development (flawed that it was, because of its centralized, paranoid and totalitarian perspectives), was a threat to these centers of capital because their own colonies might get the wrong idea

and also try for an independent path to their development.

Because World War II left the empires weak, the colonized countries started to break free. In some places, where countries had the potential to bring more democratic processes into place and maybe even provide an example for their neighbors to follow it threatened multinational corporations and their imperial (or former imperial) states (for example, by reducing access to cheap resources). As a result, their influence, power and control was also threatened. Often then, military actions were sanctioned. To the home populations, the fear of communism was touted, even if it was not the case, in order to gain support.

… you have to sell [intervention or other military actions] in such a way as to create the misimpression that it is the Soviet Union the you are fighting…

The net effect was that everyone fell into line, as if it were, allowing a form of globalization that suited the big businesses and elite classes mainly of the former imperial powers. (Hence, there is no surprise that some of the main World War II rivals, USA, Germany and Japan as well as other European nations are so prosperous, while the former colonial countries are still so poor; the economic booms of those wealthy nations have been at the expense of most people around the world.) Thus, to ensure this unequal success, power, and advantage globalization was backed up with military might (and still is).

Hence, even with what seemed like the end of imperialism and colonialism at the end of World War II, and the promotion of Adam Smith free trade and free markets, mercantilist policies still continued. (Adam Smith exposed the previous system as mercantilist and unjust. He then proposed free market capitalism as the alternative. Yet, a reading of Adam Smith’s Wealth of Nations would reveal that today is a far cry from the free market capitalism he suggested, and instead could still be considered monopoly capitalism, or the age-old mercantilism that he had exposed! More about this in the next section on this site.) And so, a belief system had to accompany the political objectives:

When the blatant injustices of mercantilist imperialism became too embarrassing, a belief system was imposed that mercantilism had been abandoned and true free trade was in place. In reality the same wealth confiscation went on, deeply buried within complex systems of monopolies and unequal trade hiding under the cover of free trade. Many explanations were given for wars between the imperial nations when there was really one common thread:

Who will control resources and trade and the wealth produced through inequalities in trade?All this is proven by the inequalities of trade siphoning the world’s wealth to imperial centers of capital today just as they did when the secret of plunder by trade was learned centuries ago. The battles over the world’s wealth have only kept hiding behind different belief systems each time the secrets of laying claim to the wealth of others’ have been exposed.

Going Global

The Reagan and Thatcher era in particular, saw neoliberalism pushed to most parts of the globe, almost demonizing anything that was publicly owned, encouraging the privatization of anything it could, using military interventions if needed. Structural Adjustment policies were used to open up economies of poorer countries so that big businesses from the rich countries could own or access many resources cheaply.

Lori Wallach, Director of Global Trade Watch, also describes in a video clip (4:30 minutes, transcript) how even the term free trade

is misleading, for the free trade agenda pushed through the World Trade Organization includes many non-trade issues, such that trade is just one small part:

The belief in free markets (or the version being promoted) was very ideological:

So, from a small, unpopular sect with virtually no influence, neo-liberalism has become the major world religion with its dogmatic doctrine, its priesthood, its law-giving institutions and perhaps most important of all, its hell for heathen and sinners who dare to contest the revealed truth. Oskar Lafontaine, the ex-German Finance Minister who the Financial Times called an

unreconstructed Keynesianhas just been consigned to that hell because he dared to propose higher taxes on corporations and tax cuts for ordinary and less well-off families.1979, the year Margaret Thatcher came to power and undertook the neo-liberal revolution in Britain. The Iron Lady was herself a disciple of Friedrich von Hayek, she was a social Darwinist and had no qualms about expressing her convictions. She was well known for justifying her program with the single word TINA, short for There Is No Alternative. The central value of Thatcher’s doctrine and of neo-liberalism itself is the notion of competition — competition between nations, regions, firms and of course between individuals. Competition is central because it separates the sheep from the goats, the men from the boys, the fit from the unfit. It is supposed to allocate all resources, whether physical, natural, human or financial with the greatest possible efficiency.

In sharp contrast, the great Chinese philosopher Lao Tzu ended his Tao-te Ching with these words:

Above all, do not compete. The only actors in the neo-liberal world who seem to have taken his advice are the largest actors of all, the Transnational Corporations. The principle of competition scarcely applies to them; they prefer to practice what we could call Alliance Capitalism.

As former World Bank Chief Economist Josepth Stiglitz notes, it is a simplistic ideology which most developed nations have resisted themselves:

The Washington Consensus policies, however, were based on a simplistic model of the market economy, the competitive equilibrium model, in which Adam Smith’s invisible hand works, and works perfectly. Because in this model there is no need for government — that is, free, unfettered,

liberalmarkets work perfectly — the Washington Consensus policies are sometimes referred to asneo-liberal,based onmarket fundamentalism,a resuscitation of the laissez-faire policies that were popular in some circles in the nineteenth century. In the aftermath of the Great Depression and the recognition of other failings of the market system, from massive inequality to unlivable cities marred by pollution and decay, these free market policies have been widely rejected in the more advanced industrial countries, though within these countries there remains an active debate about the appropriate balance between government and markets.

Activist and academic Raj Patel explains that prices do not accurately reflect the value of commodities due to so many externalities (a $4 hamburger should cost $200 for example if some environmental aspects are factored in, for example), and also notes that various leading proponents of neoliberalism are now admitting it too, in the wake of the financial crash in 2008. Furthermore, markets aren’t separate from social and political contexts in which they function, yet, business leaders and governments were all too willing to go for the simpler soundbites:

The problem with the Efficient Markets Hypothesis is that it doesn’t work. If it were true, then there’d be no incentive to invest in research because the market would, by magic, have beaten you to it. Economists Sanford Grossman and Joseph Stiglitz demonstrated this in 1980, and hundreds of subsequent studies have pointed out quite how unrealistic the hypothesis is, some of the most influential of which were written by Eugene Fama himself [who first formulated the idea as a a Ph.D. student in the University of Chicago Business School in the 1960s]. Markets can behave irrationally—investors can herd behind a stock, pushing its value up in ways entirely unrelated to the stock being traded.

Despite ample economic evidence to suggest it was false, the idea of efficient markets ran riot through governments.

Since the Cold War has ended, it is almost no surprise that today’s globalization has come in the form we see it — that is where it would have been had the Cold War not got in the way

. The World Wars were about rival powers fighting amongst themselves to the spoils of the rest of the world; maintaining their empires and influence over the terms of world trade, commerce and, ultimately, power.

Throughout the Cold War, we contained a global threat to market democracies: now we should seek to enlarge their reach.

John Gray, mentioned above, notes that the same processes to force the peasantry off their lands and into waged labor, and to socially engineer a transformation to free markets is also taking place today in the third world:

The achievement of a similar transformation [as in mid-nineteenth century England] is the overriding objective today of transnational organizations such as the World Trade Organisation, the International Monetary Fund and the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development. In advancing this revolutionary project they are following the lead of the world’s last great Enlightenment regime, the United States. The thinkers of the Enlightenment, such as Thomas Jefferson, Tom Paine, John Stuart Mill and Karl Marx never doubted that the future for every nation in the world was to accept some version of western institutions and values. A diversity of cultures was not a permanent condition of human life. It was a stage on the way to a universal civilization, in which the varied traditions and culture of the past were superseded by a new, universal community founded on reason.

Gray also notes how this western view of the world is not necessarily compatible with the views of other cultures and this imposition for a western view of civilization may not be accepted by everyone. Ironically then, using terms like Enlightenment

, freedom

, liberty

, etc, which is common in such discourse, as Gray notes, results in conformity, almost totalitarian in nature.

Going bust? The Global Financial Crisis Shakes Confidence

Around mid-2008 a financial crisis, starting in the US, spread around the world into a global financial crisis, and then into a more general economic crisis, which, as of writing this, the world has still not recovered from.

The crisis has been so severe, criticisms of market fundamentalism and neoliberalism are more widespread than before.

Raj Patel argues that the markets in their current shape have created a convoluted idea of value; value meals

are cheap but unhealthy whereas fruit and veg are often more expensive; rainforests are hardly valued whereas felling trees adds to the economy.

Flawed assumptions about the underlying economic systems contributed to this problem and had been building up for a long time, the current financial crisis being one of its eventualities.

This problem could have been averted (in theory) as people had been pointing to these issues for decades. Yet, of course, during periods of boom no-one (let alone the financial institutions and their supporting ideologues and politicians largely believed to be responsible for the bulk of the problems) would want to hear of caution and even thoughts of the kind of regulation that many are now advocating. To suggest anything would be anti-capitalism or socialism or some other label that could effectively shut up even the most prominent of economists raising concerns.

Of course, the irony that those same institutions would now themselves agree that those anti-capitalist

regulations are required is of course barely noted. Such options now being considered are not anti-capitalist. However, they could be described as more regulatory or managed rather than completely free or laissez faire capitalism, which critics of regulation have often preferred. But a regulatory capitalist economy is very different to a state-based command economy, the style of which the Soviet Union was known for. The points is that there are various forms of capitalism, not just the black-and-white capitalism and communism. And at the same time, the most extreme forms of capitalism can also lead to the bigger bubbles and the bigger busts.

In that context, the financial crisis, as severe as it was, led to key architects of the system admitting to flaws in key aspects of the ideology.

At the end of 2008, Alan Greenspan was summoned to the U.S. Congress to testify about the financial crisis. His tenure at the Federal Reserve had been long and lauded, and Congress wanted to know what had gone wrong. Henry Waxman questioned him:

- Greenspan:

I found a flaw in the model that I perceived is the critical functioning structure that defines how the world works, so to speak.

- Waxman:

In other words, you found that your view of the world, your ideology, was not right, it was not working.

- Greenspan:

Precisely. That is precisely the reason I was shocked, because I had been going for 40 years or more with very considerable evidence that it was working exceptionally well.

[Greenspan’s flaw] warped his view about how the world was organized, about the sociology of the market. And Greenspan is not alone. Larry Summers, the president’s senior economic advisor, has had to come to terms with a similar error—his view that the market was inherently self-stabilizing has been

dealt a fatal blow.Hank Paulson, Bush’s treasury secretary, has shrugged his shoulders with similar resignation. Even Jim Cramer from CNBC’s Mad Money admitted defeat:The only guy who really called this right was Karl Marx.One after the other, the celebrants of the free market are finding themselves, to use the language of the market, corrected.

Quoting Stiglitz again, he captures the sentiments of a number of people:

We had become accustomed to the hypocrisy. The banks reject any suggestion they should face regulation, rebuff any move towards anti-trust measures — yet when trouble strikes, all of a sudden they demand state intervention: they must be bailed out; they are too big, too important to be allowed to fail.

…

America’s financial system failed in its two crucial responsibilities: managing risk and allocating capital. The industry as a whole has not been doing what it should be doing … and it must now face change in its regulatory structures. Regrettably, many of the worst elements of the US financial system … were exported to the rest of the world.

Some of these regulatory measures have been easy to get around for various reasons. Some reasons for weak regulation that entrepreneur Mark Shuttleworth describes include that regulators

- Are poorly paid or are not the best talent

- Often lack true independence (or are corrupted by industries lobbying for favors)

- May lack teeth or courage in face of hostile industries and a politically hostile climate to regulation.

Given its crucial role, it is extremely important to invest in it too, Shuttleworth stresses.

However, this crisis wasted almost a generation of talent:

It was all done in the name of innovation, and any regulatory initiative was fought away with claims that it would suppress that innovation. They were innovating, all right, but not in ways that made the economy stronger. Some of America’s best and brightest were devoting their talents to getting around standards and regulations designed to ensure the efficiency of the economy and the safety of the banking system. Unfortunately, they were far too successful, and we are all — homeowners, workers, investors, taxpayers — paying the price.

Paul Krugman also notes the wasted talent, at the expense of other areas in much need:

How much has our nation’s future been damaged by the magnetic pull of quick personal wealth, which for years has drawn many of our best and brightest young people into investment banking, at the expense of science, public service and just about everything else?

The wasted capital, labor and resources all add up.

British economist John Maynard Keynes, is considered one of the most influential economists of the 20th century and one of the fathers of modern macroeconomics. He advocated an interventionist form of government policy believing markets left to their own measure (i.e. completely freed

) could be destructive leading to cycles of recessions, depressions and booms. To mitigate against the worst effects of these cycles, he supported the idea that governments could use various fiscal and monetary measures. His ideas helped rebuild after World War II, until the 1970s when his ideas were abandoned for freer market systems.

Keynes’ biographer, professor Robert Skidelsky, argues that free markets have undermined democracy and led to this crisis in the first place:

What creates a crisis of the kind that now engulfs us is not economics but politics. The triumph of the global

freemarket, which has dominated the world over the last three decades has been a political triumph.It has reflected the dominance of those who believe that governments (for which read the views and interests of ordinary people) should be kept away from the levers of power, and that the tiny minority who control and benefit most from the economic process are the only people competent to direct it.

This band of greedy oligarchs have used their economic power to persuade themselves and most others that we will all be better off if they are in no way restrained—and if they cannot persuade, they have used that same economic power to override any opposition. The economic arguments in favor of free markets are no more than a fig leaf for this self-serving doctrine of self-aggrandizement.

Furthermore, he argues that the democratic process has been abused and manipulated to allow a concentration of power that is actually against the idea of free markets and real capitalism:

The uncomfortable truth is that democracy and free markets are incompatible. The whole point of democratic government is that it uses the legitimacy of the democratic mandate to diffuse power throughout society rather than allow it to accumulate—as any player of Monopoly understands—in just a few hands. It deliberately uses the political power of the majority to offset what would otherwise be the overwhelming economic power of the dominant market players.

If governments accept, as they have done, that the

freemarket cannot be challenged, they abandon, in effect, their whole raison d'etre. Democracy is then merely a sham. … No amount of cosmetic tinkering at the margins will conceal the fact that power has passed to that handful of people who control the global economy.

Despite Keynesian economics getting a bad press from free market advocates for many years, many are now turning to his policies and ideas to help weather the economic crisis.

We are all Keynesians now. Even the right in the United States has joined the Keynesian camp with unbridled enthusiasm and on a scale that at one time would have been truly unimaginable.

… after having been left in the wilderness, almost shunned, for more than three decades … what is happening now is a triumph of reason and evidence over ideology and interests.

Economic theory has long explained why unfettered markets were not self-correcting, why regulation was needed, why there was an important role for government to play in the economy. But many, especially people working in the financial markets, pushed a type of

market fundamentalism.The misguided policies that resulted — pushed by, among others, some members of President-elect Barack Obama’s economic team — had earlier inflicted enormous costs on developing countries. The moment of enlightenment came only when those policies also began inflicting costs on the US and other advanced industrial countries.…

The neo-liberal push for deregulation served some interests well. Financial markets did well through capital market liberalization. Enabling America to sell its risky financial products and engage in speculation all over the world may have served its firms well, even if they imposed large costs on others.

Today, the risk is that the new Keynesian doctrines will be used and abused to serve some of the same interests.

Some of the world’s top financiers and officials are reluctantly accepting that the version of capitalism that has long favored them may not be good for everyone.

Stiglitz observed this remarkable resignation at the annual Davos forum, usually a meeting place of rich world leaders and the corporate elite, who usually together reassert ways to go full steam ahead with a form of corporate globalization that has benefited those at the top. This time, however, Stiglitz noted that

[There was a] striking … loss of faith in markets. In a widely attended brainstorming session at which participants were asked what single failure accounted for the crisis, there was a resounding answer: the belief that markets were self-correcting.

The so-called

efficient marketsmodel, which holds that prices fully and efficiently reflect all available information, also came in for a trashing. So did inflation targeting: the excessive focus on inflation had diverted attention from the more fundamental question of financial stability. Central bankers’ belief that controlling inflation was necessary and almost sufficient for growth and prosperity had never been based on sound economic theory.… no one from either the Bush or Obama administrations attempted to defend American-style free-wheeling capitalism.… Most American financial leaders seemed too embarrassed to make an appearance. Perhaps their absence made it easier for those who did attend to vent their anger. Labor leaders working for the … business community were particularly angry at the financial community’s lack of remorse. A call for the repayment of past bonuses was received with applause.

Some at the top, however, have tried to play the role of victim:

Indeed, some American financiers were especially harshly criticized for seeming to take the position that they, too, were victims … and it seemed particularly galling that they were continuing to hold a gun to the heads of governments, demanding massive bailouts and threatening economic collapse otherwise. Money was flowing to those who had caused the problem, rather than to the victims.

Worse still, much of the money flowing into the banks to recapitalize them so that they could resume lending has been flowing out in the form of bonus payments and dividends.

And as much as this crisis affects wealthier nations, the poorest will suffer most in the long run:

… This crisis raises fundamental questions about globalization, which was supposed to help diffuse risk. Instead, it has enabled America’s failures to spread around the world, like a contagious disease. Still, the worry at Davos was that there would be a retreat from even our flawed globalization, and that poor countries would suffer the most.

But the playing field has always been uneven. If developing countries can’t compete with America's subsidies and guarantees, how could any developing country defend to its citizens the idea of opening itself even more to America’s highly subsidized banks? At least for the moment, financial market liberalization seems to be dead.

In effect, the globalization project, an ideal that sounded appealing for many around the world, was flawed by politics and greed; the inter-connectedness it created meant that as any flaws revealed themselves, the unraveling of such a system would have far greater reach and consequences, especially upon people who had nothing to do with its creation in the first place.

More Information

The above may seem long, but many volumes could be written to expand on the above themes. Until I can get to do something like that, the following are links to some useful resources to help understand neoliberalism and its historical and current context:

- A Short History of Neo-Liberalism: Twenty Years of Elite Economics and Emerging Opportunities for Structural Change by Susan George, from a conference on Economic Sovereignty in a Globalising World, Bangkok, 24-26 March 1999

- What is

Neo-Liberalism

? A brief definition for activists by Elizabeth Martinez and Arnoldo Garcia, National Network for Immigrant and Refugee Rights, January 1, 1997 (posted at CorpWatch.org) - Has Globalisation Really Made Nations Redundant? The States We are Still In, by Noelle Burgi and Philip S. Golub, Le Monde Diplomatique, April 2000.

- The Essence of Neoliberalism by Pierre Bordieu, Le Monde Diplomatique, December 1998

- The Institute for Economic Democracy has a wealth of information.

- Program on Corporations Law & Democracy looks at the creation and development of English commercial corporations and the abolition of democratic control over their behavior. From UK-based Corporate Watch (not related to the above-mentioned US-based organization of the same name!)

- This web site’s look at projecting power introduces the link between geopolitics and economics; of the use of military to back up trade objectives.

- The Citizens’ Guide to Trade, Environment and Sustainability from Friends of the Earth gives an overview of the world trade system, the ideology, the impact on society, environment, etc.

- Neoliberalism: origins, theory, definition is a detailed look by Paul Treanor, a political thinker and writer.

- The Luckiest Nut In The World is an 8 minute video (sorry, no transcript available, as far as I know), produced by Emily James. It is a useful and light way of explaining some of the issues around free trade (in its current form) and its impact on poorer countries. Under their license, it has been reposted here. (Please note the license of this video is not covered by this site’s own license).

Author and Page Information

- Created:

- Last updated: