Police Killings Challenge U.S. "Exceptionalism"

UNITED NATIONS, May 06 (IPS) - Since being roundly chastised last fall by the U.N. Committee Against Torture for excessive use of force by its law enforcement agencies, the United States hasn't exactly managed to repair its international reputation.

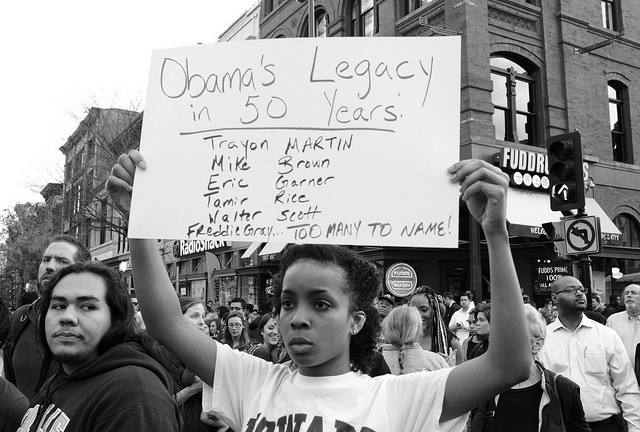

Fatal beatings and shootings of African American and Latino citizens, mainly men, by the police have continued seemingly unabated, with the latest being the widely publicised case of Freddie Gray in Baltimore, Maryland. Gray, 25, died Apr. 19 of spinal cord injuries in what has been ruled a homicide after being arrested for allegedly carrying an illegal pocket knife. Six officers have since been charged in his murder.3

The wave of cases - many caught on camera and shared via social media – have sparked a nationwide protest campaign grouped under the hashtag #blacklivesmatter.

On Nov. 28, a year after the Committee's damning report, the U.S. must provide information on what it has done to follow up on its recommendations, which included prompt investigation and prosecution of police brutality cases and providing effective remedies and rehabilitation to the victims.

"The best way to begin to bring this racism and particular police murders to an end is by what we are seeing today: massive and militant demonstrations everywhere and shutting cities down," Michael Ratner, president emeritus of the New York-based Centre for Constitutional Rights, told IPS. "We are in a special moment that rarely occurs in this country; people are mobilised and in the streets. That is the key. Our cities cannot be governed without the consent of the governed.

"But of course there are other important elements as well. The platform the U.N. CAT offered for Blacks particularly to speak out was important, very important. It gave Michael Brown's family an opportunity to be heard around the world as it did others. The conclusions of the committee were powerful and while the United States tried to ignore them, the world would not. The report gives international legitimacy to the protests we are seeing every day."

Michael Brown was an unarmed Black teenager who was shot and killed by white police officer Darren Wilson in Ferguson, Missouri. A grand jury refused to indict in his Aug. 9, 2014 death.

Brown's parents testified before the U.N. committee in Geneva last year, and U.N. High Commissioner for Human Rights Zeid Ra'ad Al Hussein cited the case in condemning "institutionalised discrimination in the U.S."

"The CAT report put pressure on the U.S. to do something and while its response was inadequate, the report's findings can be seen as the beginning of the end for the belief both in the U.S. and abroad that the U.S. is a just society toward Blacks," Ratner said.

"As the U.S. claims a human rights mantle and criticises others for racism, it becomes the world's greatest hypocrite. Yes, the U.S. is the most powerful country and can ignore the U.N., but ultimately by doing so, it will be ignored."

Ratner cited a previous instance that demonstrates how important the U.N. can be in this regard. In 1951, "We Charge Genocide: The Crime of Government Against the Negro People" was submitted to the U.N. by the Civil Rights Congress and detailed the horrendous situation faced by American Blacks.

"It received huge international press. The U.S. realized that it could not call itself a democracy and claim it was better than Communist countries if racism was so embedded in its society. Three years later the Supreme Court ended school desegregation.

"While the report was not the only reason for that change, the point is that the U.N. and particularly the recent CAT committee report has pointed to serious defects in U.S. democracy and human rights. It's hard after this report, although surely the U.S. will try, to criticise other countries' human rights and not simply be laughed at."

Because the U.S. is a state party to the Convention against Torture, it is regularly examined by the CAT committee. Its next report is due in November 2018, after which the date for the next review will be set. In general, these reviews happen every four or five years.

Alba Morales, a researcher for the U.S. Programme at Human Rights Watch, agrees that advocates have been able to use the international attention brought by these reports to strengthen their local work.

"Take the John Burge torture cases in Chicago, for example," he told IPS. "Burge was a Chicago police officer commander who oversaw the torture hundreds of arrestees in that city. Chicago advocates worked for decades to obtain accountability for those acts of torture by police, and appeared before the U.N. Committee Against Torture in 2006.

"It was only after the U.N. Committee called for accountability in that case that the U.S. government took action, eventually indicting and convicting Burge of obstruction of justice. While this was the result of many years of local advocacy, the spotlight that the U.N. report shone on these cases also contributed to the outcome."

Morales said that the United Nations can continue to welcome the voices of those directly affected by human rights violations everywhere, including in the U.S.

"The families of Trayvon Martin and Jordan Davis attended the last meeting of the U.N. Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination. Their testimony powerfully illustrated the racial discrimination that persists in the U.S. While none of these U.N. committees can enforce any judgements against the U.S. or any other country, having an international platform amplifies the voices of those who are working incredibly hard to improve the human rights situation in the U.S."

Ratner noted that U.S. racial discrimination, backed by state violence, has a lengthy and deeply rooted history that dates back hundreds of years.

"Ending the police murders and brutal treatment of Black people in the United States is no easy task," he said. "Many whites, particularly in law enforcement, are racist to the core. It is a racism that has a history since the early days of slavery and it is a racism that continues in many aspects of Black people's lives.

"Once it was called slavery, then Jim Crow, then slavery by another name, then the new Jim Crow. Yet we all know this unequal and brutal treatment of Black people must end."

Edited by Kanya D'Almeida

© Inter Press Service (2015) — All Rights Reserved. Original source: Inter Press Service

Global Issues

Global Issues