Green Recovery in Mexico A Citizens Plea

NEW YORK, Nov 23 (IPS) - The alarms warning against climate inaction have sounded for years. Almost a year into the hardest pandemic and maybe the worst economic recession my generation has seen, expert voices everywhere are claiming this to be the golden opportunity to do something to right our course and even find a silver lining in this unfortunate situation, by funding the economic recovery of COVID-19 with a green stimulus package.

This approach could help move humanity into more sustainable economic growth and towards a slightly more attainable path towards the 1.5°C goal.

As a worried citizen of the world, and more particularly, as a Mexican national who understands climate change and is concerned for my country, I ponder how Mexico should face its own economic recovery.

When it comes to Mexico, one argument suggests that given its poverty rate around 40 percent (and about 9 million more citizens possibly pushed into poverty due to the COVID-19 crisis), and the economic collapse estimated at 8-10 percent in 2020, the country cannot afford to think of climate change when drafting its recovery plans; it must worry first about how to get out of the ditch.

Governments can choose to spend recovery package funds in multiple ways and this will depend upon each country's specific circumstances. Yet, it is fair to say that regardless of those, governments should aim towards packages that spur further economic activity and create jobs, for instance, large infrastructure and mass-transit projects.

Fortunately for humanity, and for our environment, green energy and infrastructure development can be particularly effective at addressing depressed demand because they can create a relatively high amount of jobs and lay the foundations for sustainable long-term growth

, explains Stéphane Hallegatte, lead economist of the World Bank's Climate Change Group. In fact, World Bank data shows that green projects like energy efficiency and renewable energy are much more effective at job creation than fossil fuel projects.

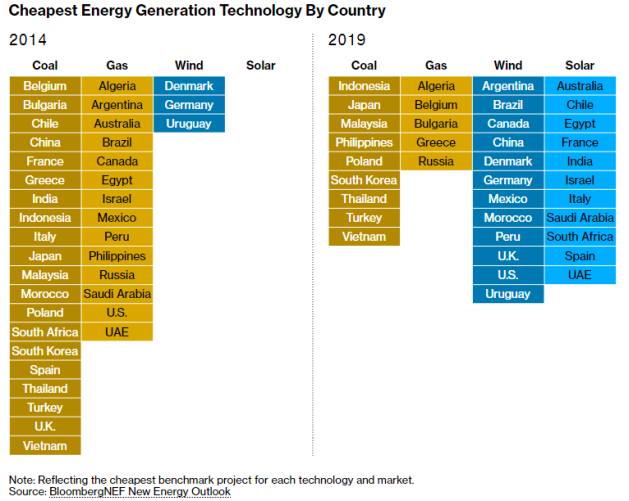

Most experts today agree that a green stimulus package can boost the economic recovery while tackling climate change. This boost can be attributed to many of those projects being low-hanging fruits of the energy transition, and also to technology which, contrary to what was true in past recessions, has brought down green energy costs to the point where, an IRENA study found, more than half of the renewable power capacity added in 2019 was cheaper than that produced by fossil-fuel sources.

A Bloomberg paper also found that Photovoltaic Solar power or Onshore Wind energy is now the cheapest source of new bulk electricity generation in countries that make up for two thirds of the world's population and 85 percent of power demand. It also discovered that the cost of storing electricity is now half of what it was only two years ago. Furthermore, we know today that investing in renewable energy creates around 2.5 times more jobs per dollar than fossil fuel projects.

Therefore, the perceived dilemma of going green vs economic development is, today, a false dichotomy.

Nations around the world have already committed large amounts of their recovery packages toward the energy transition. According to the Energy Policy Tracker, an initiative launched by six leading energy research organizations, since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic the G20 group has committed at least $346 billion USD to supporting different energy projects through new or amended policies.

Meanwhile, in Mexico, the government committed at least 3 billion USD to energy projects of which all are in the oil and gas sector. Furthermore, the administration of President Andrés Manuel López Obrador (also known as AMLO) is betting on the Mayan Train and the Dos Bocas refinery projects to spur employment and growth as a way out of the economic downturn.

So far, the only green-related unconditional policy was proposed by the Mexico City government, which committed to the expansion of the so-called ciclo-pistas

(or bike-dedicated lanes). More recently, on October 2020, the government announced an economic recovery plan comprised of 39 infrastructure projects to be developed jointly with the private sector, out of which only 5 are energy-related and not one involves renewables.

In fact, Mexico seems committed to turning back time instead of taking part in the energy revolution when, only a few years back, it was at the forefront of the fight against climate change, both internationally and at home. In late July, AMLO stated in a written memorandum that his government has the goal of increasing crude oil production to 2.2 million barrels per day by 2024; building and revamping electrical plants in Mexico's southeast, and; increasing hydroelectric power generation while capping the private sector's participation in electricity generation at 46 percent. Bloomberg described the President's wishes accurately: the higher goal of his administration is to recover Mexico's (the government's) control over its oil and electricity industries, including state-owned utility Comisión Federal de Electricidad (CFE)

.

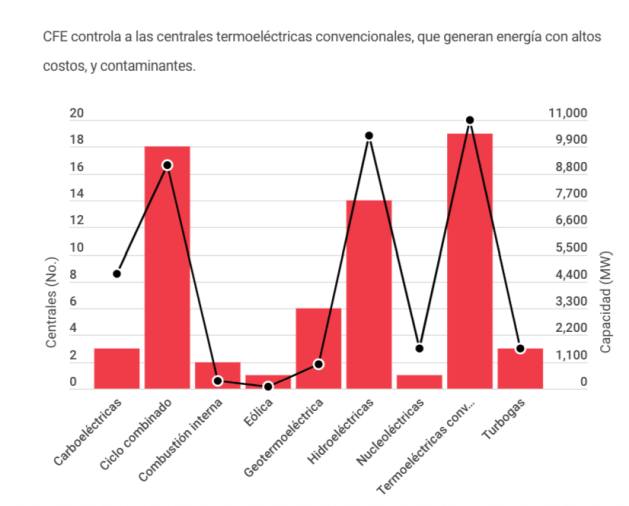

CFE was founded 83 years ago and its generation fleet has an average age of 33 years and 42 percent of its power is generated through high-cost, highly polluting technologies, like fuel-oil and gas.

CFE's thermoelectric plant in Tula, near Mexico City, and one of the four largest power plants it owns and operates, has violated the allowed limits of sulfur and sulfur dioxide in the fuel-oil it burns during four years straight. These are extremely harmful contaminants for the environment and for human health that are generally regulated by governments, as they can lead to chronic respiratory diseases, cancer and premature death.

Unfortunately, the government shows no intention of reversing its course. To this, chemistry Nobel-winning Mexican José Mario Molina said in an August 2020 Reuters interview not long before he died that, "Mexico is going backwards, back to the previous century or the one before, at a time when all the experts on the planet are in total agreement that we're in a climate crisis".

Furthermore, CFE generation plants average a cost per megawatt-hour (MWh) of $1,127 MXN, while independent power producers average $913 pesos per MWh and the ones signed through long-term electricity auctions - mostly wind and solar plant - run at about $423 pesos per MWh, according to data published by the state energy regulator (Comisión Reguladora de Energía, or CRE). In fact, modernizing the state-run utility and its fleet would require investments in the order of $9 billion USD, according to analysts.

Early in his administration, AMLO halted the long-term electricity auctions. Later, in May 2020, the Mexican Official Gazette received a request for publication of a public policy proposal by the Energy Ministry that would effectively bar new renewable projects to be connected to the electric grid, claiming that a higher volume of this type of electricity generation that is considered as intermittent,

would endangered its reliability.

These measures were met with deep concern from the private sector, as they would endanger thousands of the renewable sector's jobs and close to $30 billion USD in investments. The measures were immediately challenged in court and in August 2020, the Mexican Center for Environmental Law and Greenpeace obtained a definitive suspension. As a result of this ruling, preapproved renewable energy projects will be allowed to continue construction and operation.

Measures to give back monopolistic power and market-share to CFE have also been rolled-out in benefit of Pemex, such as disappearing strategic alliances with third parties; halting indefinitely oil rounds for private participation in oil and gas exploration and production projects, and; extensive fiscal incentives to weather the tough times brought by the COVID-19 oil price crash.

The government is betting its economic recovery partly on the new U.S.-Mexico-Canada trade agreement, which is a solid bet. Yet it is also relying on two state-owned companies that had their glory days in the middle of the twentieth century and the construction of what are considered white elephant — or at least financially suspect — projects: an oil refinery in AMLO's home-state and a train that increases connectivity between the Mayan regions in southern Mexico with the rest of the world.

Mexico should pay attention to what multiple other nations are doing in order to kickstart the economy post-COVID-19 and adopt solutions to its needs. A large number of those will likely be related to energy efficiency, renewable power and distributed generation, green infrastructure and climate adaptation projects.

Including these measures in its policy toolkit would benefit Mexico greatly in the short -and medium- term economically, and in the large scheme of things would help us avoid lagging behind the next big global energy revolution.

It should also work on initiatives like the recent issuance of a Sovereign Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) Bond by Mexico's Finance Ministry, in hand with the United Nations Development Programme, which was a first of its kind.

This move should increase Mexico's earmarked spending for sustainable development programs engulfed by the UN's 2030 agenda, which includes sustainable development and mitigation of climate-related risks.

More importantly, we need to stop championing the old ways: the fossil fuel economy and state-run inefficient monopolies. We should instead be looking towards the technologies of the future, towards space and the oceans (instead of the ground), and, on our way, put our grain of salt towards that 1.5°C goal, which, by the way, is perhaps one of the few band-wagons it is worth jumping on today.

Tania Miranda is an Economist with a Master's degree in energy policy, and has worked for over 6 years in the public sector, on trade and investment promotion as well as on public diplomacy and international relations. She was born and raised in Mexico City and strives to promote stronger climate action in her home-country and abroad. She's based in NYC.

© Inter Press Service (2020) — All Rights Reserved. Original source: Inter Press Service